Prudential fiscal stimulus

ZEW Public Finance Conference, 4 May 2023

Alfred DuncanUniversity of Kent |

Charles NolanUniversity of Glasgow |

This project is supported by research funding from UKRI Grant Ref: ES/V015559/1

The conventional view (the Greenspan put)

|

Stimulus policies increase moral hazard.

Anticipating to be rescued in downturns, firms might take more risk today.

|

The theorem (Arnott-Greenwald-Stiglitz)

|

Policymakers can reduce moral hazard, and increase efficiency,

by taxing or regulating the complements of moral hazard and/or

subsidising the substitutes for moral hazard.

Doesn't align with concerns about the Greenspan put. We ask, when does fiscal stimulus reduce the moral hazard problems that concern prudential policymakers? |

Our contribution

|

|

Intuition behind our result

Absent intervention

Intuition behind our result

Introduction of the wage subsidy

Intuition behind our result

Firm's risk allocation response

Intuition behind our result

Intuition behind our result

|

Labour supply is a complement to firms' inside wealth.

|

Related literature

|

Macropru

Information economics

|

The macroprudential externality

The macroprudential externality

Three ingredients

- Anonymous unrestricted trade in aggregate-state contingent securities.

- Agency costs restricting trade in idiosyncratic-state contingent securities.

- Risk aversion over individual specific states.

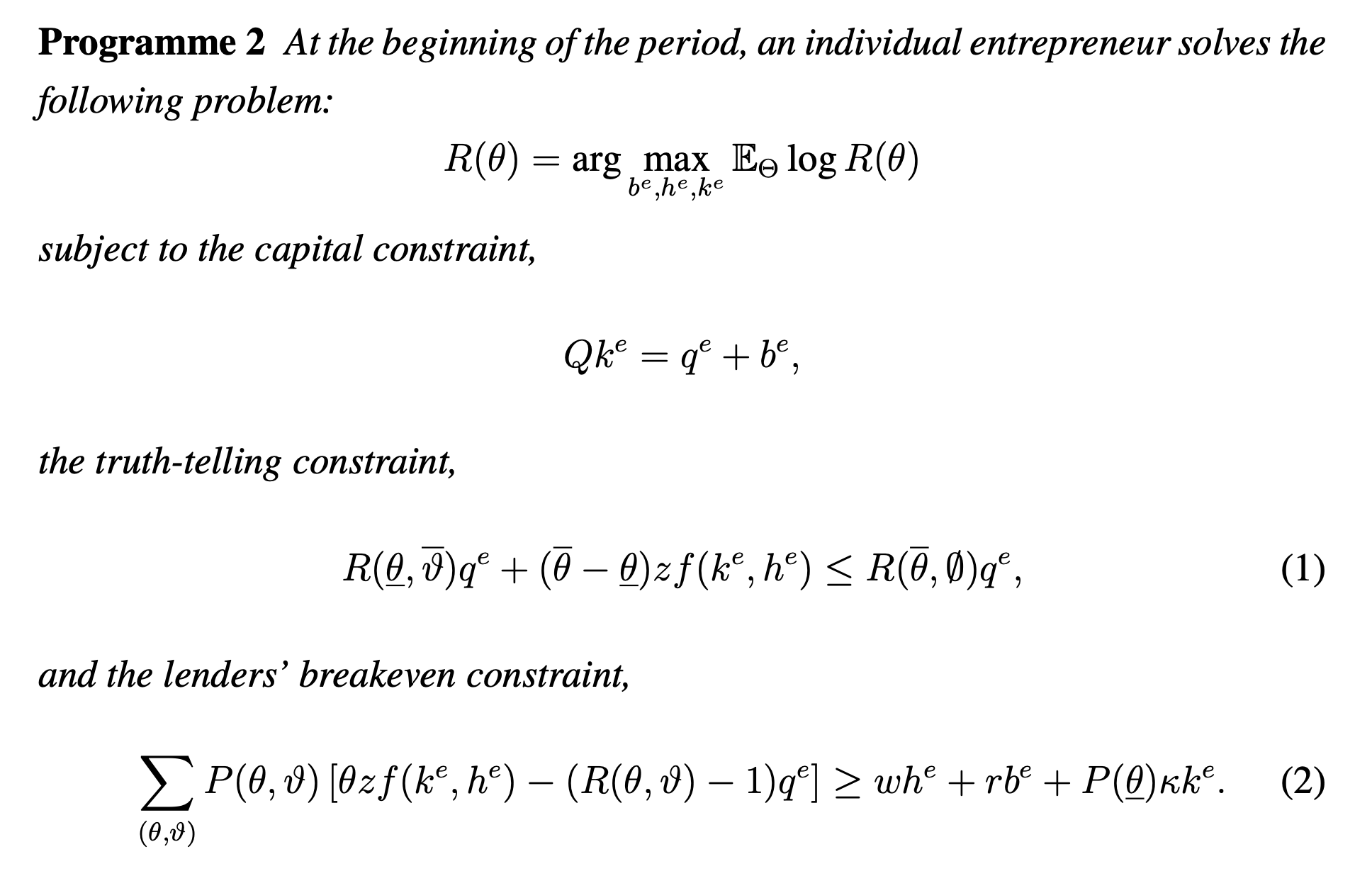

The entrepreneur's intratemporal problem

|

Extension |

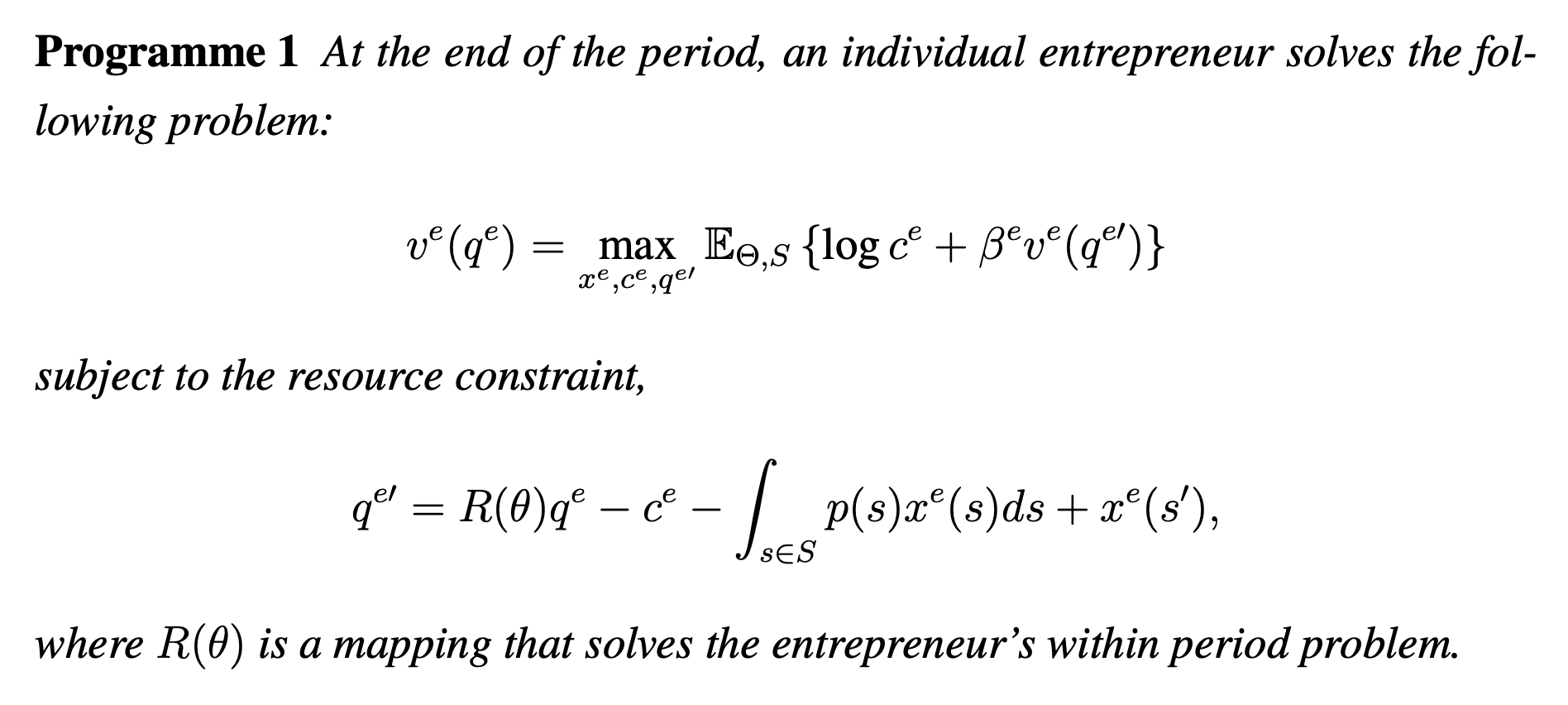

The entrepreneur's intertemporal problem

|

captures trade in aggregate state contingent securities. Markets for aggregate risks are complete. |

The household's problem

|

subject to |

captures trade in aggregate state contingent securities. Markets for aggregate risks are complete. |

Factor markets

|

|

|

Factor markets

|

|

|

Factor markets

|

|

|

The competitive allocation of aggregate risk

Optimal macroprudential policy

Under optimal policy

Optimal macroprudential policy leans against

- fluctuations in leverage, and

- entrepreneurs' exposure to risk shocks.

The macroprudential externality

Cyclical risk is a complement to downturn moral hazard.

Entrepreneurs accept too much cyclical risk,

amplifying the cost of moral hazard in downturns,

Arnott-Stiglitz: Regulate cyclical risk (macroprudential)

Optimal wage subsidy policy

Optimal wage subsidy policy - example with log utility

|

Proposition

Let

a. Optimal wage subsidy:

b. Output is completely stabilised in response to uncertainty shocks, and is proportional to total factor productivity. |

|

Optimal wage subsidy policy - example with log utility

|

Under the competitive equilibrium in the absence of wage subsidy policy, real output follows Under the optimal wage subsidy, real output follows Real output is proportional to total factor productivity in both regimes, but only responds to fluctuations in leverage and risk under the competitive equilibrium. Under the optimal wage subsidy regime, output does not respond to uncertainty shocks. |

|

How the intervention works

Benefit

Wage subsidies

- complement firms' wealth,

- encourage precaution during expansions, and

- decreases financial frictions in downturns.

- First order welfare gain.

Cost

Wage subsidies

- introduces a distortion between labour supply and demand,

- Second order welfare cost.

Quantitative exercise

Exercise

|

Wage subsidy simple rule

|

We propose the following simple rule:

where |

Expected welfare effects of wage subsidy simple rules

Welfare gain is expressed as a share of business cycle welfare losses.

Shaded area indicates 90% credible interval.

Persistence of TFP shocks

Welfare gain is expressed as a share of business cycle welfare losses.

Extensions

Commitment vs discretion

Optimal wage subsidy policy generates an ex post distortion, that reduces efficiency. The benefit of the policy derives from changes in agents' actions ex ante.

In the flexible price model, a policymaker optimising under discretion does not use wage subsidy policies.

Sticky prices

(Dixit's critique) If the margin that the policy is acting on is distorted,

then the Arnott-Stiglitz logic doesn't necessarily hold.

New Keynesian markups act on same margin as policy. We verify that New Keynesian frictions do not overturn the result.

In fact, in the NK extension, the commitment problem is less severe, as there is an ex post incentive to stimulate the economy.

Summary

|

We present a model where moral hazard generates a macroprudential externality.

In lieu of aggregate demand externalities, there is still a role for fiscal stimulus. If the stimulus programme complements inside wealth, like a labour subsidy, then it will

|